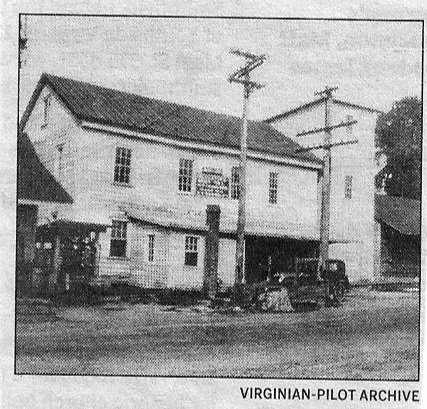

N.H. Byrd’s Store

The ultimate location of this store would be the second store as you enter Chuckatuck coming from Suffolk. Mr. Byrd’s first store was located just beyond the grist mill on the left-hand side of the road, heading toward Smithfield. It was primarily a gas station built by Mr. W.C. Mathews for his sons around 1916 and leased to Mr. Byrd in 1928. That building still existed and, in 2007, had been used for several types of businesses. Mr. Byrd’s ultimate destination was directly across the road from Chuckatuck High School, which was in operation from circa 1938 to 1960. In discussions with Jack Byrd, he noted that although built as an auto repair garage and gas station, it also served as a local grocery store and restaurant. The restaurant did not fare well and was closed after a year or two of operation. Bill Harvell, who was instrumental in starting the local fire department, was the main mechanic for Mr. Byrd at one time. There were many local patrons, but the location was significant for many CHS students as it allowed some older boys to go over and have lunch off the school grounds. There were times when the Byrd boys were there, and music was the venue of the day. On many occasions, Charlie, Oscar (“Popeye”), Jack, and Gene would be sitting around the pot-bellied stove strumming and singing songs. Charlie Byrd became an international sensation with his 12-string guitar and the Bossa Nova. He even recorded an album with a song entitled “Chuckatuck”. Like many of the other stores, it was sold, and in this case, to Jimmy Brasfield. Ultimately, the building was torn down in the 1960s.

Glover’s Store at Gloversville

This store was built in the 1930s by Mr. C.W. Glover, founder of Gloversville. The store was constructed right after the Depression and closed in the early 1940s after approximately ten years of operation. It was a general store that also served as an auxiliary post office. Mail from Chuckatuck for residents of the Cedar Brook and Holiday Point area, if not picked up at the main post office, would be delivered there for future delivery by Mrs. E. L. Bowden. This store served the local tenants from several farms in the area. In addition to the store, there were four houses in the area of Gloversville, which ran from the railroad bridge to the African American ball diamond. The store has since been torn down, but one of the two houses that now stands there is an original, while the other is new. There was once a Glover’s store on Longview Drive, but it closed before the Depression. Not much is known about that store.

Doyle Meat Plant

Doyle’s Store

Grist Mill

Col 1121819

Trips to the Chuckatuck Grist Mill

By John Edwards

I came across a paper bag a couple of weeks ago while sorting through some things in my office.

This is not just any bag. It's made of very heavy, durable brown paper that, had it ever been used, which it had not, would have held corn meal.

It proclaims its contents, had it ever been used, to be five pounds of "Chuckatuck New Water Ground Type White Screen Corn Meal." The bag went on to identify the miller as "Chuckatuck Enterprises and further defined the company as "millers of high grade meal since 1820."

This small memento brought back memories of trips to Chuckatuck when I was quite young, as well as the preparations for those trips.

My father always planted a small field of white corn. In the summer, that became the source of our sweet corn. Roasting "ros'n" ears, we called it, though we never roasted one. We boiled the ears just the same as today. Once we had purchased a chest freezer, we would freeze packages of corn for use during the winter. Corn and butter beans, corn pudding, and corn fritters were all good, and they lasted well into the winter months.

The remainder of the white corn was allowed to ripen and was picked, then kept separate from the "field" corn that was used as hog feed. The white corn was stored apart in a small, framed-up corner of the corncrib.

After school or on Saturdays, one of my chores was to shell the white corn with a hand-driven corn sheller. The wooden box that contained the sheller sat atop four sturdy legs. A large flywheel was turned by hand, and the corn was fed into the top of the contraption. Inside, a large, round disc with small, raised nodes turned against the corn ears, removing the kernels. The kernels were dropped out of the bottom into a five-gallon bucket from which they could then be poured into burlap sacks.

The stripped cobs were also saved. Most were taken to spread onto clay galls in a field with particularly heavy soil. Some were saved to be used as fire starters. Dipped in kerosene, they burned quite hot to get a woodstove fire going.

Shelling corn was one of the most satisfying tasks on the farm. Watching kernels pile up in the bucket as stripped cobs flew out the other end of the sheller was almost enjoyable at a time when many chores weren't.

Later, we loaded bags of shelled corn into the old Chevrolet pickup truck and hauled them to Chuckatuck. The mill operation was an absolute fascination to a child. Watching the large water wheel turn and corn meal emerge made for about as interesting a few hours as a six-year-old could spend.

I've written previously about the mills that dotted Isle of Wight and Surry, and won't re-plow that ground except to say that gristmills were a vital part of a rural economy up until store-bought flour and cornmeal became available.

Transportation drove that change, naturally. As trucks and cars became commonplace (well before my time) and roads were built to accommodate them, factory mills replaced community gristmills, and a way of life came to an end.

The Chuckatuck mill continued into the 1950s, when it was converted into an ice plant that remained in operation for several more decades.

(Originally published as a "Short Rows" column in The Smithfield Times Dec. 18, 2019.)

Gwaltney’s Store

G.L. Gwaltney

This store was next to the intersection of Routes 10 and 125. We believe the Peck/Brittain/Ramsey/Pinner/Jones/G.L. Gwaltney store, built in the early 1800s, is the oldest working store on record. A circa 1900 tin picture of this store features a sign on the front that reads “Nat Peck’s Cheap Store.” After that time, it was run by the Brittain family. Later, E. E. Jones and his wife, Blanche Pope Jones, rented directly from Dr. L.L. Eley. When Lafayette Gwaltney purchased the store from Dr. Eley in 1929, a step was added as you entered, providing additional headroom for the basement located beneath the store. Rumor has it that in those early years, the basement might have been a speakeasy or something similar, but others say it was just an accumulation of stuff. In a conversation with Frank Spady, Jr. in 1999, he indicated that during a remodeling job in the 1920s, the main floor of Gwaltney’s store was lowered to accommodate living quarters added upstairs. Mr. Spady also mentioned that a bar once existed in that basement. There is some confusion about who was running the store at the time the floor was lowered, but Paul Gwaltney, Lafayette’s grandson, stated that it was one of the first things his grandfather did when he bought the store, as it created a more level entry. Although robberies have been minimal in this area, Mr. Gwaltney was robbed and shot three times in 1970. He made his way over to his home next door, told his wife, and then returned to the store, where he waited for Dr. Eley and Dr. Thomas to arrive. When Mr. Gwaltney passed away in 1991, his son, G. L. “Spunk” Gwaltney, Jr., took over the store and worked there until he was unable to continue in 2009. It was then that the door was secured, as it had not been profitable in later years at all. It is worth noting that the store in 2009 was a genuine step back in time to the mid-1800s. In 1948-1950, Drex Bradshaw, along with many other locals, worked as a summer employee for Mr. Gwaltney, especially on Fridays and Saturdays when he was particularly busy. Possibly the most dedicated employee in his later years was Frank Buppert, who was born and raised in Chuckatuck. Frank could be spotted in a crowd of people 24/7 because he always had a toothpick in his mouth. He even kept it there when he smoked, which he did for many years. After he retired from the Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Frank spent most of his time helping Mr. Gwaltney in the store.

Just like other stores, most purchases were made on credit, with very few paying until the end of the month or when the crops came in. From the Norfolk Ledger-Star dated Monday, June 14, 1971, the following is quoted from an interview with Mr. Gwaltney. “I’ve worked many a long hour and shared many a disappointment with my friends, especially during the real hard times some years back, but sitting here thinking about it now, well, I’ve had the best opportunity a man can have in life, and that’s having a chance to know a lot of good people and being able to help them when they needed help. That’s what this career and life had been for me,” he said. Lafayette Gwaltney had his system of welfare during the hard times. It wasn’t anything elaborate or complicated. “People had to eat whether they had money or not. It was as simple as that,” he said. According to Paul Gwaltney, the room attached to the store was used for dances on Saturday night, and at least once a month, the Lone Star Cement Company held a meeting there, consuming several cases of beer. Paul also remembers having a basket full of hog heads sitting just inside the door during hog killing time. They were a delicacy for some of the workers in the area.

Ice House

C.C. Johnson’s Store

Early Johnson’s Store

The chronology for the C. C. Johnson store goes something like this. It is believed that it was built by E.C. Ramsey (date unknown) and run by him for a while. In 1891, Samuel C. Webb and Susan M. Webb, his wife, deeded a ¼-acre lot to M. W. Crumpler and Charles Bernard Godwin Sr. Mr. Crumpler sold his 50% interest to Mr. Godwin in 1892. An early 1900s picture of the store reveals signs that read “Godwin” and “Chuckatuck Post Office”. The store was likely operated by C. H. Pitt in 1935, when he deeded the entire stock in that store and the adjacent Pitt store to his daughter, Mary, and her husband, C. C. Johnson. In 1937, Mr. Godwin leased his store to Mr. Johnson for a five-year term at $18.75 per month. A deed transferring the store and ¼ acre from Mr. Godwin to Mr. Johnson, dated January 17, 1940, states that the lot was known as the “Meador Store Lot”. Mr. Johnson ran the store until the mid-1960s when he leased this building and the “little” store to Wesley Doyle. In 1968, the store caught on fire and was not rebuilt. The memories of Mr. C.C. Johnson, Jr., described that store in depth and will not be repeated here.

J.J. Johnson’s Store

J.J. Johnson’s Store

This store was just down the road (beginning of what we called the ridge), yet not far from the intersection where Gwaltney’s, C.C. Johnson’s, Spady’s, Owen’s, and Moore’s stores were located. The original J.J. Johnson store was a small wood-frame building with living quarters upstairs for two brothers of Mr. Johnson. The store sold penny candy, some groceries, and gas. In 1948, a cinder block building was constructed adjacent to the smaller, framed building and would become known as “Johnson’s Self-Service.” There was a small auto garage at the back of this building. In the new store, they had a beer license, meat that needed to be cut, and they upgraded their grocery selection. Corn, herring, and codfish were staples and were stored in large wooden barrels packed in salt. Like other stores, credit was a way of doing business, and patrons paid when they could. If they did not, and there were occasions when it happened, no court actions were ever taken, as best Jesse J. Johnson, Jr. can remember. Adjacent to the “Self Service” store was an automotive garage that was built and run by the Johnsons. The Self-Service store closed in the 1970s, and the building has been used for several other ventures. The large garage, now known as Dale’s Garage, remains the local automotive repair shop.

Lone Star Cement Corporation

Before we begin discussing the Lone Star Cement Corporation, it would be prudent to explain the primary ingredients in cement. Webster defines cement as: Any of various construction adhesives consisting of powdered, calcined rock and clay materials that form a paste with water and can be molded or poured to set as a solid mass. Marl, as defined by Webster, is: A mixture of clays, carbonates of calcium and magnesium, and remnants of shells, forming a loam used as fertilizer. Calcined as defined by Webster: to heat (a substance) to a high temperature but below the melting or fusing point, causing loss of moisture, reduction, or oxidation.

These three definitions outline the primary ingredients in cement and, to some extent, the process by which it is produced. Marl, although listed as fertilizer, is the prime ingredient in cement. As a fertilizer, it is beneficial due to its lime content.

The following discussion will take you through the process of digging the materials used in Portland Cement. Portland Cement was a trade name, and, as defined by Webster, a hydraulic cement made by heating a mixture of limestone and clay, containing oxides of calcium, aluminum, iron, and silicon, in a kiln and then pulverizing the resultant clinkers.

Marl pit, Chuckatuck, VA Dec. 1910

Original postcard

In May 1924, the Giant Portland Cement Company conveyed the property designated in Chart Number 1 (within Nansemond County and adjacent to Chuckatuck) to the Virginia Portland Cement Corporation. In 1926, the same area was transferred to the Lone Star Cement Corporation. Lone Star shut down its operation in 1971 when the cost of doing business, due to EPA requirements, made it unprofitable. Pollution from the furnaces that heated the mixtures in South Norfolk was the main reason for the closure. However, there was a marl pit and a hammer mill on land owned by sisters Annie and Lucy Upshur, which we are certain predates the establishment of the Giant Portland Cement Corporation in 1924. The Upshurs mined marl for use as chicken feed, fertilizer, and as a driveway material.

The Upshur house, located behind the current Suffolk Water Plant, was ultimately torn down by Lone Star due to its proximity to a large vein of marl. We have no pictures of this house, but those who remember it were amazed by its size and the contents, including old Indian paintings and items from the turn of the century. The house predated the Civil War and Capt. Upshur had an integral part in the Powell Wharf, which was either on or adjacent to his land. Lucy and Annie lived there until the early 1950s, when Lone Star Cement Corp. purchased their land, having previously dug very close to it. Alex Moore told Harvey Saunders Jr. that Miss Lucy and Annie had some high-class parties at their house in the 1930s. In later years, it was run down with chickens and pigs living on the first floor of the home.

The information that follows comes from discussions with Harvey Saunders, Jr., whose dad worked for the Lone Star Cement Corp. and was their last employee in the Chuckatuck area. The pictures, commentary, and drawings are from his collection and recollection of the Marl pit operations in and around Chuckatuck. Archie Fronfelter, who had been working for Lone Star in Waverly, Virginia, since he was 16, came to Chuckatuck in 1934. He lived in a company house next door to Mr. Willie Staylor, the on-site superintendent. Archie was running the drag line when they encountered a graveyard fairly close to the Upshur home, which we believe was determined to have been a slave burial ground. That island is still intact and visible now, having been preserved by the Marl Company.

Meeting of Lone Star personnel in Harvey Saunders’ backyard 1954

Harvey Saunders photo

In 1938/39, Harvey Saunders, Sr., went to work for Lone Star as a mechanic, having left his job as foreman of the Butts Farm. During his tenure, he compiled a record of all employees, including their hire dates and dates of departure. He was responsible for the overall maintenance of all equipment used in the digging, processing, and shipping of marl and blue mud to the South Norfolk plant. During the war years, the demand for concrete was so great that Lone Star operations in Chuckatuck operated 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, to meet the country's needs. The number of employees at this company's Chuckatuck location ranged from 25 to 35 at its peak. Mr. Saunders, Sr., was the last employee to leave when the company shut down its operation and sold off all of its equipment in 1971.

The two major components of cement were marl and blue mud. Both of these were readily available in the Chuckatuck area. Marl, having been created by being underwater some 35 million years ago, and blue mud, which was still within the river adjacent to Ferry Point farm and the surrounding area, were abundant and easy to mine.

Marl had been found by drilling test holes from the Nansemond River north to the Nansemond/Isle of Wight County line and beyond. The vein, as delineated on the charts, was approximately 1 mile wide and 5 miles long from the river to the Isle of Wight County line. However, additional test holes were drilled at Mogarts Beach, north of Smithfield, with good results. The depth of this vein ran from 90 to 120 feet; therefore, the pits were within that normal depth range. The washer plant was built on the banks of the Nansemond River, in the area of the Pembroke house, so that once the marl was cleaned, it could be loaded onto barges and sent to South Norfolk, a 5-hour one-way trip, for processing.

We believe it is best to break the mining into three categories for ease of understanding. First, we will discuss the mining of the marl. Secondly, we will cover the transport of the marl to the washer plant. Thirdly, we will examine the washing of the marl and loading for transport.

Initially, the equipment used for mining was a small drag line. Shortly after Lone Star purchased the mining rights, it bought a new 200-ton Byrcus Erie drag line for $1 million. This larger one was needed due to the depth of the pit and the amount of material they had to move. This dragline was an electric unit that required a 2,000-foot extension cord to bring in power from VEPCO. The main power line was 11,000 volts, and the extension cord to the drag line was 2300 volts. This extension cord was approximately 3 inches in diameter and was wound on a large spool attached to the undercarriage, beneath the 200 tons of pig iron at the rear of the dragline. The maximum distance away from the 11,000-volt power cord was 2000 feet. The cabin on the crane was three stories high and constructed of tongue-and-groove wood on a steel frame. It had a 140-foot boom and a 5-cubic-yard bucket that was large enough to fit a pickup truck. Here is a picture of the bucket emptying marl into rail cars. (from the collection of Harvey Saunders, Jr). The dragline ran on sets of rails on pallets, which were moved by the dragline, thus giving it unlimited mobility as well as a 360-degree swing. On occasion, the dragline bucket would hit a tough block of marl and would be unable to break it up without doing damage to the large teeth on the bucket. At this point, Mr. Saunders, Sr. would get into the bucket and be lifted out to the general area (over water) near the trouble spot. It was here that he would lower a sleeve of dynamite down into the water onto the bottom. With the primer cord attached, the crane operator would slowly swing him away from directly over the blast area and, on signal, would push the plunger. A geyser some 200 feet high would erupt from the water pit. This was a real treat for Harvey Saunders, Jr. when he had the opportunity to ride with his dad. Mr. Fronfelter, one of the crane operators, would swing them around 360 degrees for a real thrill. Harvey. Jr. says, “This was better than any Disney ride”.

The movement of the marl, once dug, was loaded onto side-dump train cars that were initially moved by coal- or steam-powered locomotives, and later by diesel locomotives. We only have pictures of the diesels and little to no information on the coal and steam locomotives, except that they had a water tank adjacent to the natural lake for a water supply. Due to sparks coming from the coal burning, there was always the potential for fires alongside the tracks, so Harvey Saunders, Jr., and Clyde “Buck” Kelly were the two unofficial firemen to keep track of the train movements and put out fires when they were started. We have several pictures of the diesel locomotives and the train cars in the archives at the GCHF. When you examine the photographs showing the tracks, you will notice that they were not very straight or level; however, they served their purpose, and we are aware of no derailments. The locomotives were always moving slowly, and several of the kids in the area, this writer included, would hitch a ride down to the washer plant and back every so often. I suppose we considered being a hobo and jumping the train, but the operator would slow down for us to get on board the locomotive.

Lone Star Cement Co. processing plant on Nansemond River - 1940s

Harvey Saunders’ family collection

Once the cars reached the washer plant, they first dumped each car into a large hopper adjacent to and just below the tracks, allowing the material to fall through a screen. This allowed several workmen with jackhammers to break up the larger chunks of marl so the hammer mill could handle them. The hammer mill was essentially a crusher designed to break down larger particles into smaller ones. Once through the hammer mill, the materials were sent to the washer, a 50-foot-long, 50-foot-wide, and 4-foot-deep trough with paddles featuring holes that moved back and forth, washing impurities such as clay, sand, and rocks out of the marl. On one occasion, a large blue rock, approximately 3 feet long and 2 feet wide, fell onto the screen. With men working with jackhammers, they could not break it up and asked Mr. Saunders what to do with it. He said to throw it into the hammer mill, then had second thoughts about that. It was removed, and the Smithsonian Institution later identified it as a meteorite. It stayed out by the washer plant for years and ultimately disappeared. Unofficial rumor has it that a professor from UVA had a great interest in this rock and might know something about its location. Another item removed before the hammer mill was a whale vertebra, which was carbon-dated to be 30 million years old. One of these vertebras is in the hands of Harvey Saunders, Jr’s son, and one may be in Waverly, VA, which was last seen being used as a doorstop in a local store.

Arthur Joyner standing by Lone Star train, 1940s

Joyner family photo

As the material exited the washer plant, it was moved by conveyor belt to the stowage area and awaited loading onto a barge, if one were available. A mobile conveyor was used for this purpose, while the one from the washer plant was stationary. Mr. Ozie Porter of Gloversville worked in the area of the washer plant and was responsible for moving any marl that fell from the conveyor belts back onto those belts. He worked for Lone Star for 31 years, retiring in 1963. There were usually six barges loaded every two or three days, and at least one mud barge to be picked up en route to South Norfolk off of Ferry Point farm. The crane for the mud barge was also used to remove silt from the barge staging area, as the current going in and out tended to fill in that area every few months. Arthur Joyner was one of the primary mud barge operators as well as a train operator.

Fresh water was needed to run the washer plant, and the first hole that was dug just northwest of the washer plant revealed sufficient groundwater to do the job. The next freshwater area moving northwest (toward Highway 125 and Chuckatuck) was a natural pond that provided water for the steam locomotives as well as the best fishing hole in the area. The rails for the train would extend a reasonably short distance at the beginning and remained south of Highway 125 for several years. Once they had water for the washer plant, they moved up to Highway 125 on the northeast side of the track and dug two huge lakes. The second one was adjacent to Cedar Creek, and ultimately, the earth wall between the creek and the lake caved in, making this a tidal lake. This lake was an excellent fishing area for all types of fish. Once Lone Star reached the washer plant, they came back north and dug the last hole before crossing the road. This was the best swimming hole (adjacent to Mr. Glasscock’s field). We had a float and a diving board, both of which were donated by Mr. Saunders. An overpass was built in 1945 to keep the train out of traffic at all times. The overpass has been updated but still covers the rail bed, now serving as a road between the Suffolk water plant and the area of the washer plant. With the drag line across the road, they had a long way to go to the Isle of Wight County line.

Between 1956 and 1971, the company expanded further north, up to and across the Chuckatuck Creek, continuing to the Isle of Wight County line, where it stopped digging. In 2010, charts showing the history of the Lone Star project were available.

Chart number 1 shows the original land area that was transferred from the Giant Portland Cement Company to the Virginia Portland Cement Company, dated 1926.

Chart number 2 shows the movement of marl up until 1945, when it crossed the road. Between 1926 and 1945, the marl was removed from the Kelly farm and the area adjacent to Mr. Glasscock. Lone Star had to build a barn for the Kellys since they would destroy an existing one. The marl hole behind Marvin Winslow’s house on RT 125 was our later swimming hole and the one that got the most attention in later years.

Chart 3 shows the amount of marl removed from 1956 through the shutdown in 1971.

Chart number 4 is color-coded to easily identify which areas were worked on and where the power cable and railroad were placed.

Chart 5 shows the location of the washer plant in 1926, as well as all of the land owners where the marl had been located and would be removed.

Between 1926 and 1971, the Lone Star Cement Corporation was an integral part of Chuckatuck. We have evidence of meetings with senior corporate officials at the home of Mr. Harvey Saunders (picture of such a meeting). Also, once a month, corporate officials would gather at Gwaltney’s Store on a Saturday afternoon for informal discussions and the consumption of beer, we are told.

For anyone who lived in the area during this period (especially the younger folks), the Marl holes provided some great entertainment. Swimming, diving, frogging, duck hunting, and, yes, a trash dump were all in the cards. There was only one accident, date unknown, when a young negro boy drowned in one of the lakes, and it was then that Lone Star posted its No Trespassing signs. That, however, did not deter the younger group, this writer included, as we continued on swimming and hunting, always trying to avoid the game warden and taking cover as the train passed by when we were swimming. I am sure the train operators knew we were there, given the ripples in the water from our swimming and diving. That is why the marl hole behind Marvin Winslow was so important to us, because it was somewhat isolated from the road and railroad, and we did not have to worry about the law. Skinny dipping was a natural for us as the urge to swim could come at any time, and a bathing suit was not a necessity. Rumor has it that one local girl would sneak down to this hole and announce herself as the boys swam in the nude, limiting our trips to the diving board or getting dressed. On several occasions, our clothes would take a short trip into the bushes from their original spot close to where we were swimming, which made retrieval somewhat awkward but not impossible. Riding your bicycle off the diving board as fast as possible was also a great sport. After the first time, we realized that a rope needed to be tied to the bike because it did not float very well, even with two inflated tires. Frogging at night was a “real trip,” mainly due to some of the water snakes, like the water moccasin, that were prominent in and around the marl hole shores, looking for frogs as well. The principal at Chuckatuck High School, Mr. Lew Morris, loved to go gigging and had several encounters with snakes. He always won these arguments as well as those as our principal.

Here, you will find a list of personnel who worked for Lone Star, along with specific data about each individual.

The charts listed above will be available on the website after the book is published.

(I am waiting for this data from Harvey, Jr.)

Willie Saunders’ Store (Andy Gump’s)

This was a store built for W.G. Saunders, Jr.’s father, Willie Saunders, whose nickname was “Andy Gump”, in his later years after moving from Everets. It was built on the site where Jimmy’s Pizza and Subs and Dr. Thomas’s office are now. It was a general store with a very limited selection of items and candy. There was a gas pump that primarily supported W.G. Saunders, Jr.’s trucks. Bill Saunders tells us that one of W.G.’s truck drivers hit the store and almost knocked it off its foundation. The store was opened circa 1940 and closed circa 1950.

Saunders Supply Company

B.W. Godwin

formerly Godwin Mill

Moore’s Store

Moore’s Store

Pinner / Owen’s Store

Pinner / Owen’s Store

This was a relatively small one-room store with limited goods and services, and was in and out of operation until circa 1960. There was an apartment over the store where the owners lived, as was the case in many of the stores. The Pinners originally owned the Owen’s store and may have housed the first post office in Chuckatuck. However, in later discussions with Frank Spady, it is possible that a building directly across the road from the Pinner home housed the first post office.

We do know that the post office was located in Owen’s store, then moved to the Jones/Gwaltney store, and ultimately to Moore’s store when Mr. Moore became the postmaster at Chuckatuck. When Matt Crumpler used Owen’s store as his office, he rented a portion of the room to Mr. J.R. Chapman for use as a barbershop. Ultimately, this barber chair was a part of the Chapman home and was used for cutting hair until the mid-1950s. There was an article written in St. Luke’s newsletter dated Spring 2008 by Chiles T.A. Larson, which stated, “My wife has strong ties over in nearby Chuckatuck. Her favorite aunt, Lillie Clark Owens, and seven additional relatives are buried here in the churchyard. Bernice spent many summers with her Aunt Lil, who, with her husband Clifton Owen, owned and operated a general store in the community. After her husband became incapacitated, Aunt Lil ran the store by herself and was well known and loved by all who knew her for her generosity to the needy.” This building was still standing in 2025 and was used for housing.

The “Little” Pitt Store

The store to the left of Johnson’s Store was built in the very early 1900s for Charles Henry Pitt by Jesse Frank Johnson, a general contractor. Mr. Pitt’s daughter would later marry Mr. Johnson’s son. Mr. Pitt sold the contents of the store in 1935 to his daughter, Mary Pitt Johnson, and her husband, Charles Cleveland Johnson. Later, the little store and the room that connected it to Johnson’s Store were used for storage. This little store was also used in later years as the polling place for Chuckatuck.

Pictured (left): Pitt’s store

Pictured (right) Left to right: Pitt’s store, Johnson’s store, Gwaltney’s store

White’s Radio/Mr. White

Wilson Spady’s Store

F.A. Spady’s Store

This store had a varied beginning. “Uncle” Matt Crumpler, great uncle of Frank Spady, Jr., ran the butcher shop across from the grist mill and needed a place to do his night paperwork. He rented the Owens’ store (which was to the right of the Pinner home, left of the 7-11 in 2026) to meet this need, but realized it would be better to add on to the already existing Spady auto repair shop next door to their house than to pay rent. Thus began the Wilson “Foots” Spady Store. “Foots” was Matt Crumpler’s great-nephew and brother to Frank Spady, Jr. The items carried in this store were somewhat limited and might be considered a company store. Workers from Mr. Crumpler’s meat market were paid, and, as in most stores, patrons were those who worked for the store owner; thus, many came up the hill to his store, operated by Wilson Spady, for many of their necessities.

This store was closed for business circa 1960. Wilson “Foots” Spady passed away in 1981. I (Drexel Bradshaw) know of a community member who attempted to store a set of “unlawfully removed” fender skirts under the counter in this store. The subject vehicle was parked in front of Moore’s store at night, with a set of skirts that were needed by someone else. A 10-year-old boy removed them and then had to return them because “Foots” knew where they came from. The name of this person shall be held in confidence by this writer. Frank Spady, Jr. relayed the following story that “Foots” hated rats so bad that he would sneak out to the store at night, flip on the lights, and shoot them with a shotgun. The only problem was that on one occasion, he blew holes in his drink box at the back of the store, which cost a great deal of money in those days.